Numerical optimisation of satellite swarm design for radio interferometry around the L4 point

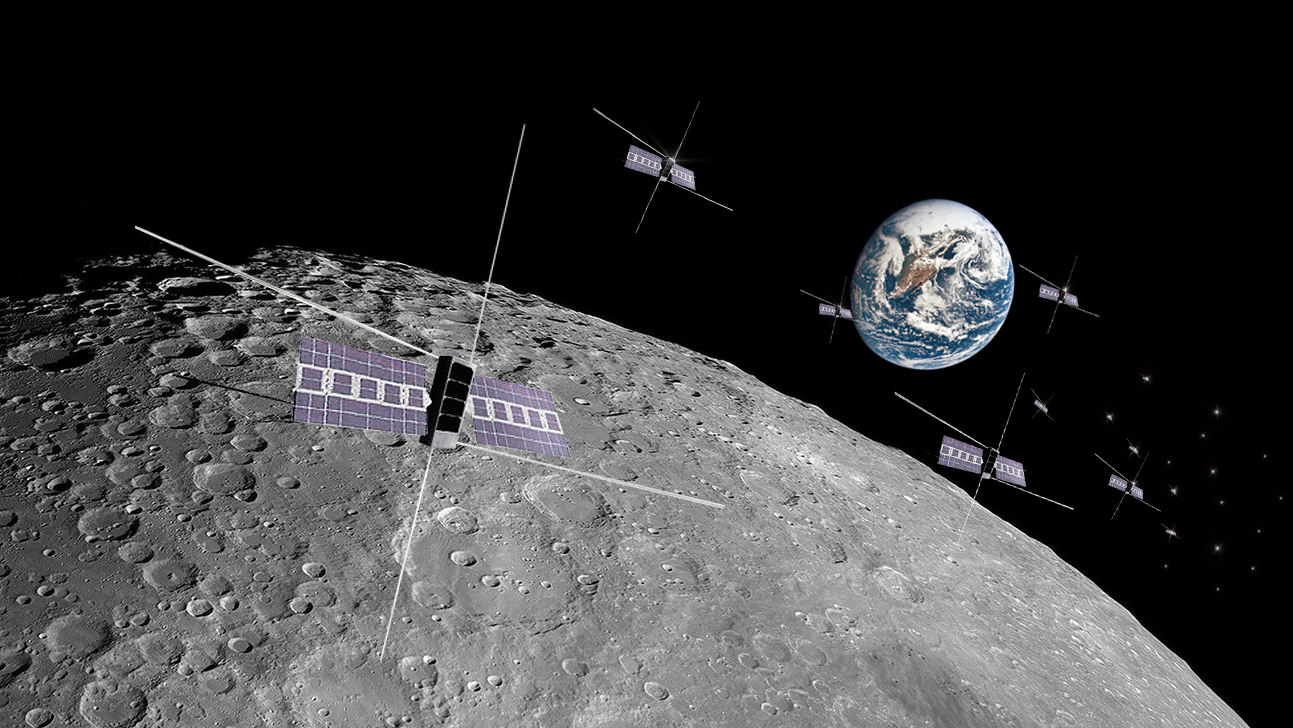

On this page I will attempt to summarize my thesis and its results as best as I can, in simple English and without (too) much technical depth. In this thesis I used evolutionary optimisation algorithms to search valid satellite constellation designs for the OLFAR radio interferometer mission concept around the 4th Lagrangian point in the Earth-Moon system, employing only passive formation flight to operate for at least a year in orbit. The found designs demonstrated viable mission lifetimes of up to three years in orbit using passive formation flight.

This work resulted in methods which were used to find suitable designs for up to 35 satellites which met all mission design parameters for a full year in orbit, flying in close proximity using only passive formation flight. For this work I was awarded an 8,0 and the title of Master of Science in Aerospace Engineering.

Readers interested in all of the details in much more technical detail are recommended to read the full thesis, of which a digital copy is provided on the bottom of this page.

The OLFAR mission concept

OLFAR (Orbiting Low Frequency ARray) is a mission concept that is being developed by the Dutch space sector, aiming to establish a large scale radio interferometry constellation in space to map the celestial sphere in the spectral region below 10 MHz. This region is nearly entirely inaccessible from Earth due to the Ionosphere, and it is expected to contain signals dating as far back as the early formation of our galaxy. The OLFAR mission aims to deploy the interferometer in a low orbit around the moon, using the moon as a shield against Earth’s interference.

One of the biggest challenges face by mission designers and engineers working on this concept is finding orbits in the low Lunar environment which are actually suitable for radio interferometry. To understand what this means, it is necessary to cover the basics of radio interferometry first.

Basic radio interferometry

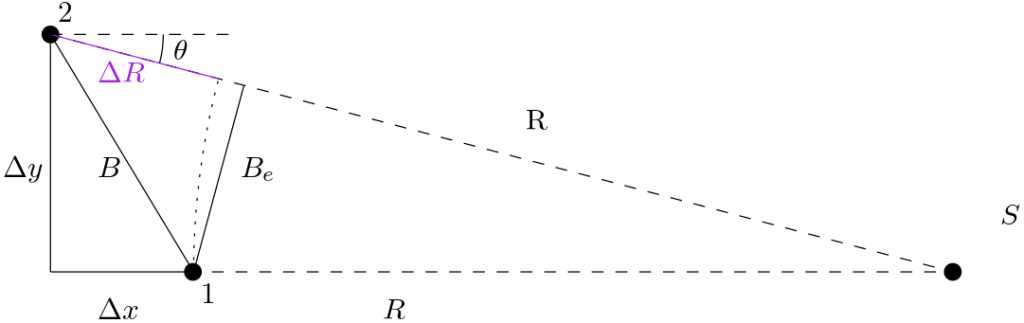

With radio interferometry we combine the measurements of two different antennae by comparing the interference between two different measurements, this allows us to extract additional information from a measurement, but more importantly to also obtain much sharper measurements than ordinarily available. This is particularly important for the field of radio astronomy, where telescopes can be required to have diameters of hundreds of meters to achieve sufficient resolutions. The most important parameter of a single interferometric measurement is the baseline, the relative position between two antennas when the measurement was taken.

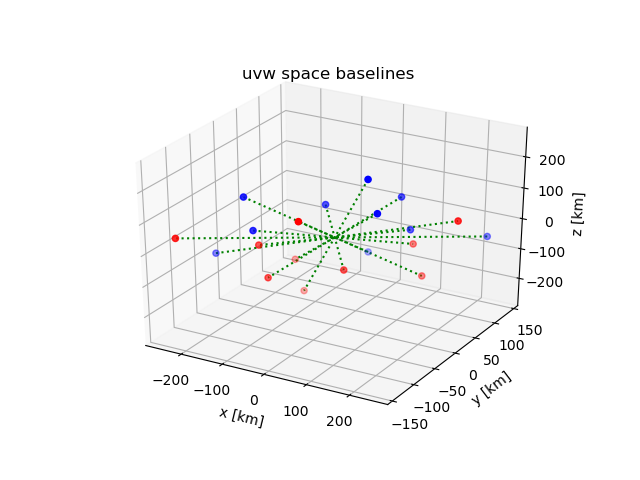

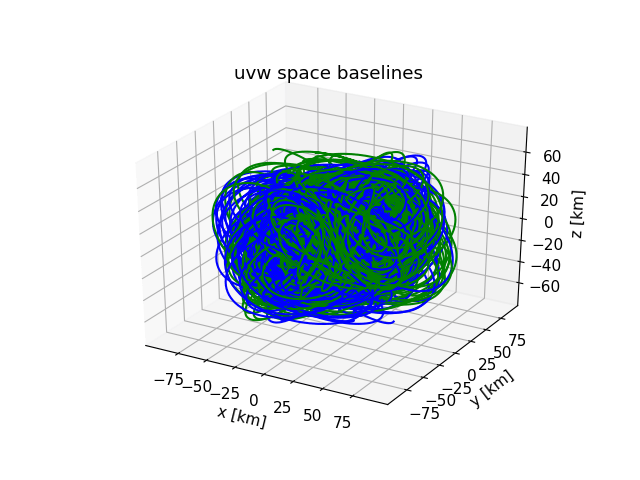

Baselines are commonly expressed in a centralized frame known as uvw space, where all different baselines used for a measurement are shown. Without going in to too much technicalities, it is important that the uvw space is filled out as much as possible over the duration of a mission. This means that the interferometer needs a dense and broad coverage of baseline sizes and orientations, in order to be capable of imaging anything in sufficient detail.

One of the main requirements for radio interferometry is that the relative velocities between satellites needs to be very small, preferably in the order of centimetres per second. Achieving this in Lunar orbits is extremely difficult for a constellation with esteemed sizes of 50+ elements, and this is why I became interested in studying alternative deployment locations for the OLFAR concept.

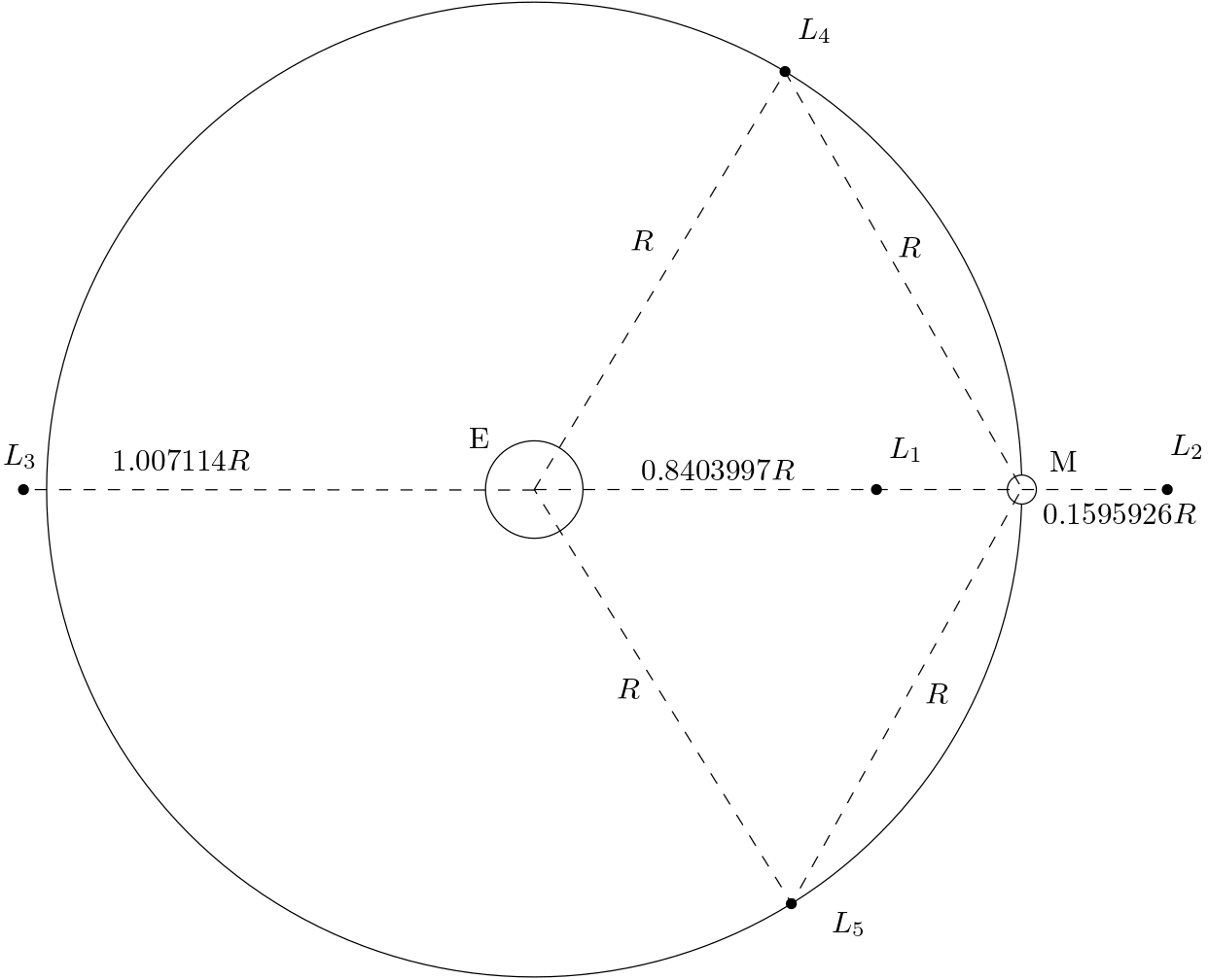

The 4th Lagrangian point

The deployment location which I deemed to be most promising, and most interesting to study, was the 4th Lagrangian point in the Earth-Moon system. Lagrangian points are equilibrium points in the barycentric three-body problem where the gravitational pull of the Earth and Moon cancel out in the co-rotating reference frame. This is a complicated way to say that an object placed at exactly the right place relative to the Earth and Moon can stay there indefinitely, as long as the conditions are exactly right.

In practice this is of course not the case, as real-world orbits are much more complicated than those described by the three-body problem. Even though orbits around L4 will not be stable indefinitely, constellations in orbit of this point will benefit greatly from being near an equilibrium location in the Earth-Moon system. The potential gradient driving the main evolution of the satellite orbits will be near-uniform across the satellites in the swarm, meaning that a bunch of satellites can stay together for much longer than if they were placed in other orbits in the Earth-Moon system.

The low potential differentials between swarm satellites also yields very low relative velocities in the co-orbiting satellites, making L4-centric orbits specifically well-suited for radio interferometry. The low relative velocities would allow a radio interferometer to use very long integration times, increasing the system sensitivity and reducing the strain on on-board radio processing systems.

The major downside of L4-centric orbits is the exposure to Earth’s radio interference, which is estimated to be ~9dB stronger than the target background signals. This provides a challenging environment for measurements, but it is not deemed to be impossible to resolve with the option of very long integration times. It would take much more research to find out how the mission concept should be changed to adapt to this environment, but my research continued on the notion that it is possible in order to look at L4-centric orbit designs.

Radio interferometer swarm design as an optimisation problem

Designing satellite swarm orbits for the purpose of radio interferometry is difficult, the OLFAR mission requires all satellites to stay within 100 km from each-other, while also maintaining a minimum distance for collision safety. A hundred kilometres may seem like a large margin, but this is extremely narrow for spaceflight, especially when we are considering passive formation flight. In addition to this narrow range of motion it is required that the relative velocities between satellites stay as low as possible, with a maximum of 1 meters per second.

This set of requirements is challenging, especially for a full year in-orbit using passive formation flight. There are near-infinite possible orbit and constellation designs which may be considered, but only a handful might meet these conditions. The expression of finding a needle in a haystack is apt, especially when larger swarm configurations are to be considered. I opted to look towards evolutionary algorithms to search this haystack for me, as these algorithms would be capable of finding suitable designs, if they existed. Before this could be done however, I needed to device a way to define swarm design for radio interferometry as an optimisation problem. In order to effectively use optimisation algorithms it is important to keep the solution space (set of viable solutions for a problem description) as small as possible, as it will generally become more difficult to find the needle the larger the haystack.

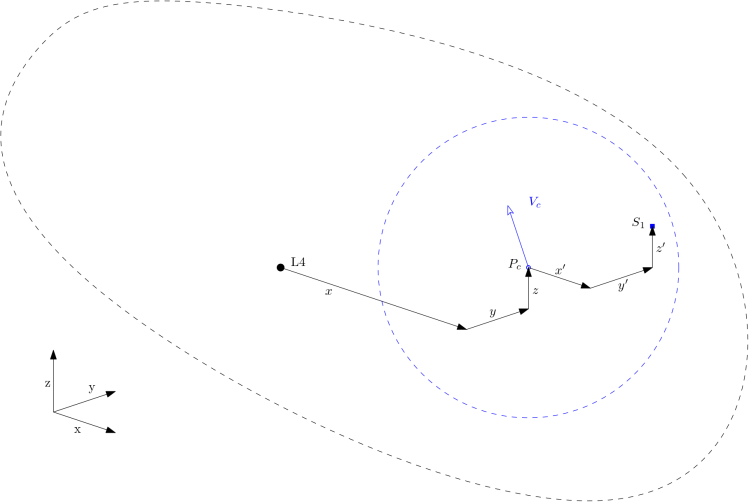

In order to severely reduce the solution space the design of a swarm was based around a central core position (Pc), which was placed relative to L4 using a single position vector. Satellites are distributed in a 100km diameter sphere around the core, and the entire swarm shares an initial velocity vector.

The resulting problem description has 6 + 3N variables for a set of N satellites, which is the smallest possible non-rigid method of defining a swarm design.

Cost function and problem constraints

To finalise the optimisation problem is it necessary to define a cost function and a set of boundaries for the solution space. The cost function is a method on which the algorithm relies on to evaluate how well-suited a specific swarm designs is for the described problem. In this case it means that as part of the cost function the orbit of a design needs to be calculated over the course of a year, and the resulting motion needs to be evaluated against the mission requirements. It was chosen to use a penalty-based cost function, penalizing a design for (temporarily) breaching any of the set mission requirements.

Calculating satellite orbits around L4

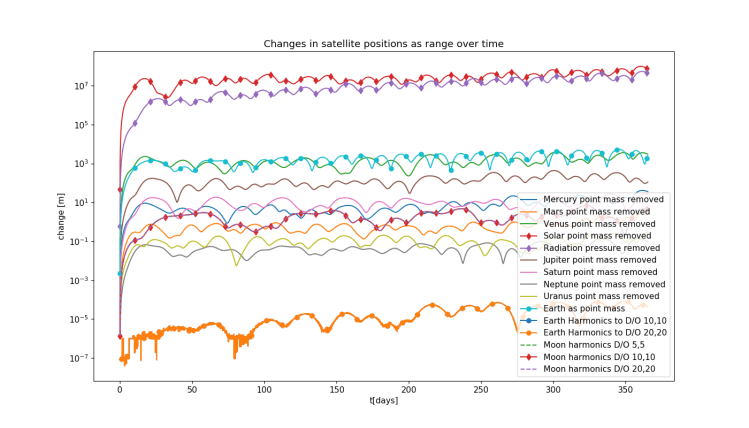

Satellites in orbit are exposed to a large variety of different forces, or perturbations, which all effect how the orbit of the satellite develops over time. In an ideal computer model one would want to consider all of these forces to calculate future satellite orbits, but the resulting model would require a supercomputer to solve in a reasonable timeframe. To design a effective and usable model it is important to know which perturbations are absolutely necessary to include, and how to best implement them.

| Source | Sun | Mercury | Venus | Earth | Moon | Mars | Jupiter | Saturn | Neptune | Uranus |

| Models | PM | PM | PM | PM | PM | PM | PM | PM | PM | PM |

| RP | SH | SH |

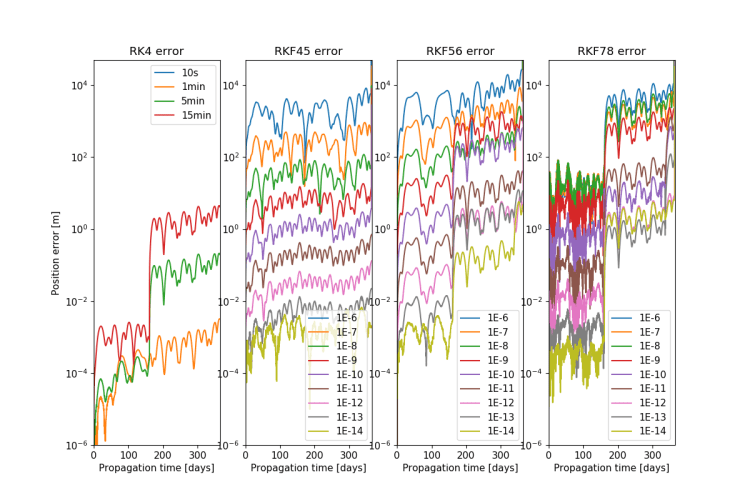

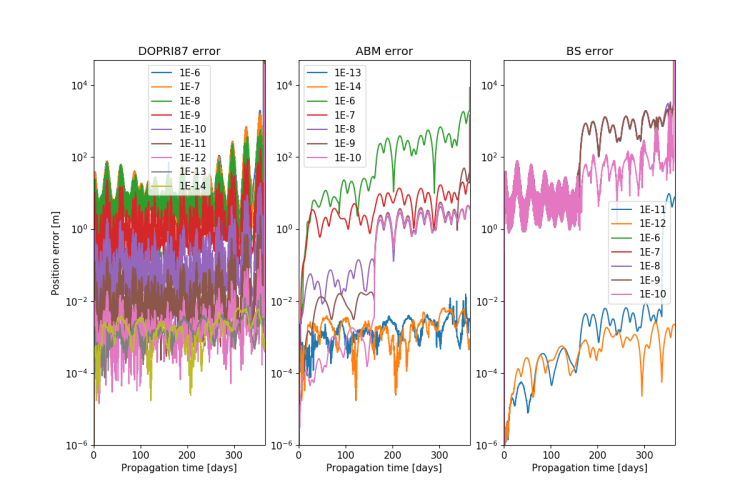

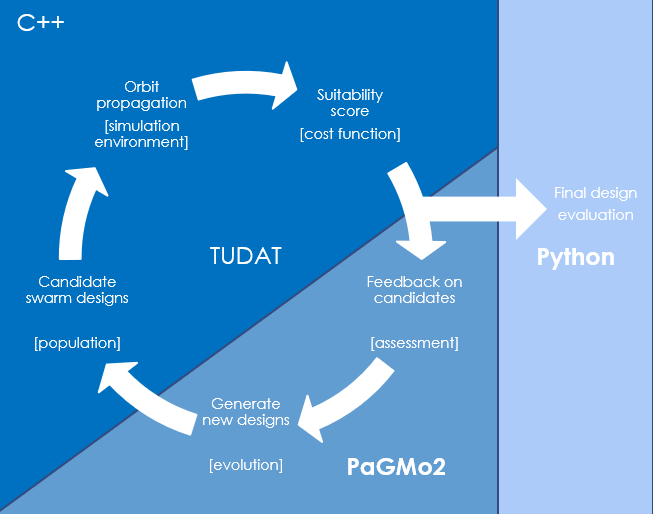

This is a topic on which I spent close to two months to design my numerical model for calculating satellite orbits around L4 for the purpose of optimisation. To build this environment I relied on the TUDAT C++ toolbox developed by the faculty of Aerospace Engineering, which made it trivial to set up very detailed simulation environments using recent scientific models. When all possible perturbation models are included it will take over 22 seconds to evaluate the orbit of 2 satellites for a full year, which is problematic when you consider an optimisation may require up to tens of thousands of evaluations. In designing the simulation environment the main goal was to retain as much accuracy to the slow reference model as possible, while making the calculation time suitable to work with.

There are two primary avenues to approach this problem, through the environment model (what forces do we model?) and the technical approach to the calculations (how do we run the calculations?). To achieve the time-savings which I required I needed to consider both, and thus I studied the effect of individual perturbation sources and different propagation techniques for a pair of satellites in a L4-centric orbit. For the details of that study refer to Chapter 5 of the thesis, on this page I’ll skip straight to the conclusion.

In order to retain sufficient accuracy compared to the reference orbit it was necessary to model a broad set of perturbing forces, with the exclusion of the gravitational pulls of Mars, Saturn, Neptune and Pluto. Both for the Earth and Moon a spherical harmonic model was necessary, but not with degrees and orders higher than (6,6). Paired with a switch to a Runge-Kutta Fehlberg 45 propagation scheme the calculation time for the satellite orbits could be reduced from 22.4 to 0.8 seconds, while retaining an accuracy of 3.3 meters in global position and 3.6 cm in relative satellite positions after a year in-orbit.

Optimisation architecture and implementation

The architecture of the optimisation process refers to how the previously described is solved. It was already decided to rely on evolutionary algorithms, but there is a wide variety of potential implementations to run this problem on hardware. I spent several weeks testing different suitable architectures and algorithm variations against a small-scale test problem to determine the most efficient setup for the interferometry swarm design, and again this will not be covered in detail on this page. Interested readers are instead referred to Chapter 6 of the thesis.

I concluded on the use of the differential evolution 1220 algorithm developed by ESA, which showed to be most capable to solve this problem definition. The final implementation of this algorithm relied on 32 parallel processes running in different CPU cores, acting as a singular large-scale optimisation algorithm with a population of 1522 individuals.

Satellite swarm designs for radio interferometry

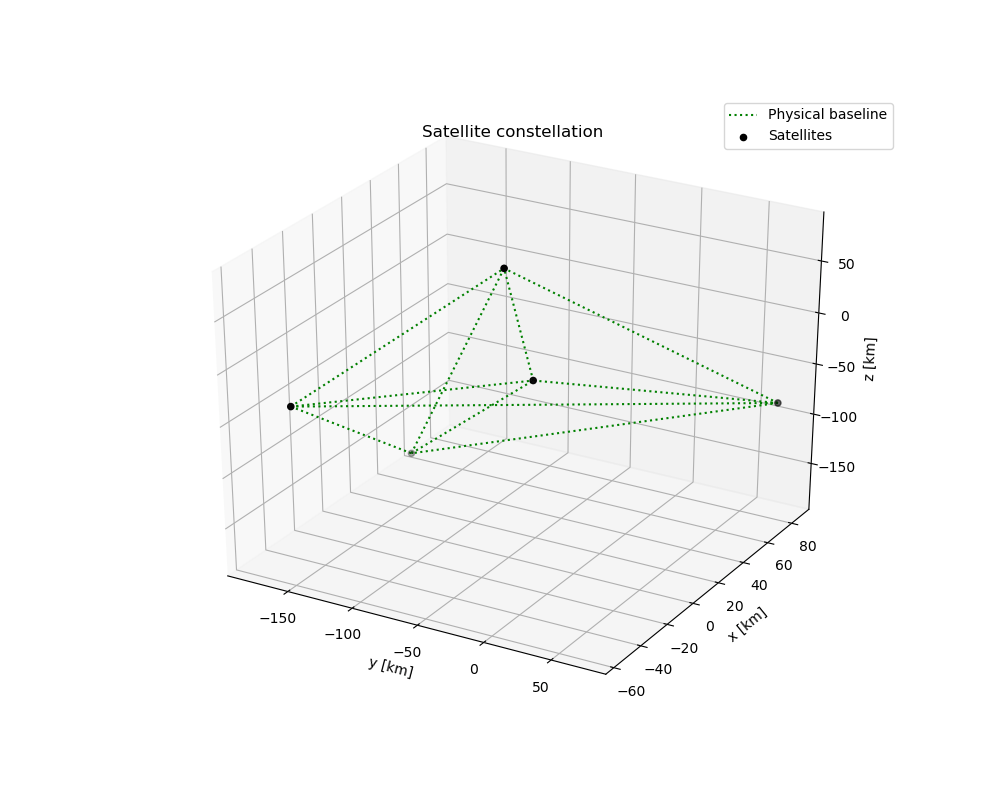

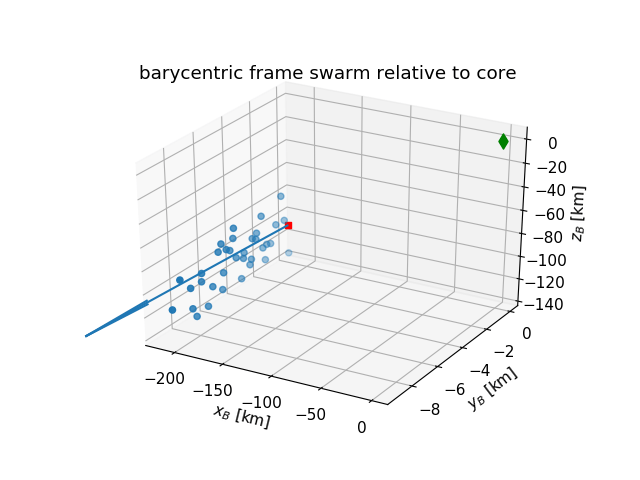

Over the course of 6 weeks the optimisation algorithm was intensively used on both my own hardware and a dedicated server of the faculty, and during this time the algorithm found hundreds of unique designs for satellite swarms using passive formation flight, with sizes of up to 35 satellites. There are simply too many results to discuss them all, so instead this section will highlight one of the largest designs for a 35-satellite interferometry swarm.

The display of the initial configuration may not be the most impressive result, but this design in question meets all set mission requirements for at least a full year in orbit around L4 using passive formation flight, and it demonstrated to have a viable lifetime of up to 3.5 years in-orbit without corrections.

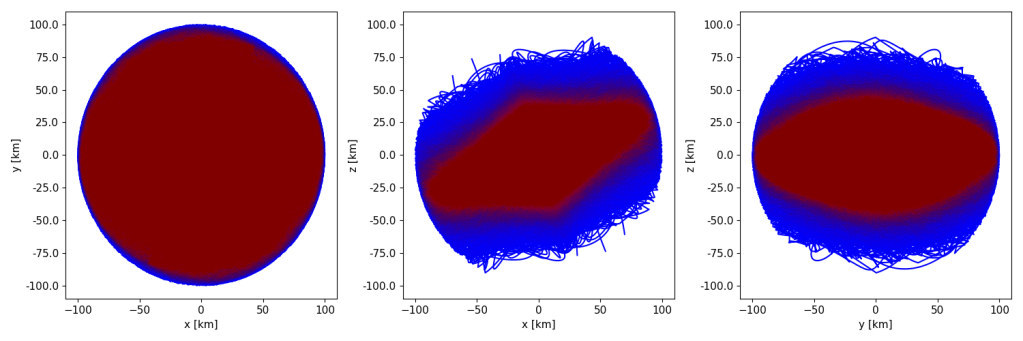

This result is achieved through a process that is described as “swarm folding”, a recurring motion where the swarm continually folds over itself, caused by distributing the swarm as a column in the barycentric z direction with a uniform initial velocity. This process is best shown in motion, as it is hard to picture using text.

By designing the swarm as a pillar configuration in the barycentric z axis and using uniform initial velocities, half the swarm will overshoot the common orbit around L4 and half the swarm undershoots. Combined with the periodic nature of L4-centric orbits this creates a repeating pattern, which greatly improves the stability of a swarm design for passive formation flight.

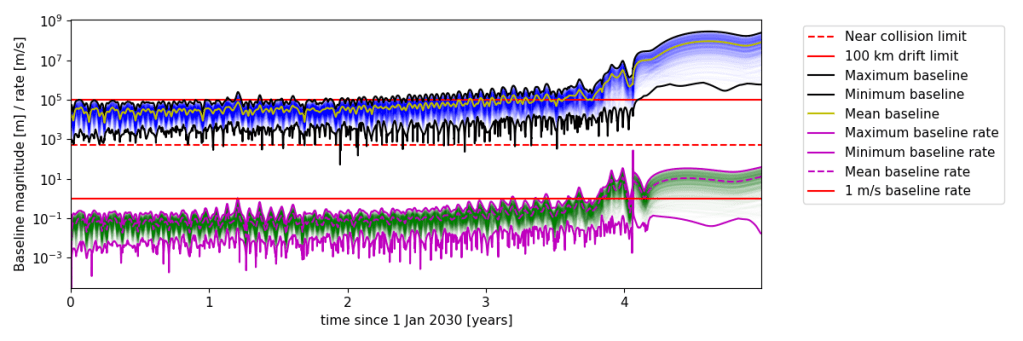

The resulting folding motion is stable for at least 8 months in-orbit, before it noticeably starts to decay under the influence of third-body perturbations. Even though the harmonic nature of the motion decays, the stable nature of this motion persists for much longer, allowing the swarm to retain general cohesion for up to three years in-orbit using passive formation flight. This can be seen in the baseline evolution of this specific design, which shows 4 distinct phases in its lifetime.

During the first year in orbit, or the design period, this design meets all mission requirements without problems. Despite only being designed for a year this design is still largely usable during the second and third year in orbit, it is only after 3.5 years that the average baseline grows too large to use for radio interferometry. After 3 years and 8 months a noticeable shift in the evolution shows the design falling out of the L4-centric orbit, and the swarm rapidly decays before being slingshot out of the Earth-Moon system by the Moon just after 4 years in orbit.

It is shown that L4-centric swarm designs can achieve significant mission lifetimes while relying on passive formation flight only, through the application of the folding motion. Evaluating the uvw baseline profiles achieved during this period also shows that such designs perform exceptionally well in achieving proper distribution for interferometric imaging:

These results show that near-ideal imaging conditions may be achieved by such designs, although there are clear limitations related to the orientation of the Lunar orbital plane. Achieving out-of-plane relative motion is extremely difficult for a cohesive swarm, and this might only be resolved through the use of multiple indepentdent smaller swarms.

Conclusions & Recommendations

The primary conclusion of the thesis is that L4-centric orbits are very suitable for the deployment of a radio interferometry satellite constellation relying on passive formation flight, if the Earth’s interference can be dealt with. L4-centric orbits offer the capability to design large swarms flying in close proximity through the process of swarm folding, yielding substantial mission lifetimes even without considering active control. The resulting patterns of motion are exceptionally well-suited to imaging with interferometry, as the folding motion provides ample uvw space coverage even in short timeframes.

It is shown that it is possible to fully rely on passive formation flight in L4-centric orbits for swarms with sizes up to 35 satellites, and it is expected that even larger designs may be viable. Said designs show ample promise to support a radio interferometer for the OLFAR mission, and may yet be improved substantially by studying the potential implementation of active formation control to longer sustain the folding motion and the swarm’s orbit near L4. It is also shown that it is viable to design satellite swarms through the means of evolutionary algorithms, and that the developed methods are sufficiently effective to do so. However, improvements will need to be made to continue using these methods to search for even larger designs.

A large number of different recommendations are given for future research based on this work, among which is a large set of suggestions of improvements for the methods developed during this thesis. Now that the general trend of passive swarm design solutions is known, the optimisation process can be made much more efficient by adjusting the problem definition and search boundaries. It is expected that much larger designs may still be found using the improved methods, and that the idea of design through optimisation could also be useful to search for Lunar orbits. Refer to the full thesis for the full list with other derived topics of research.